Humble Disciple

Active Member

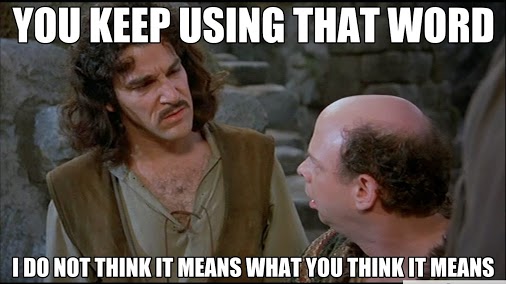

There is a difference between Biblical inerrancy and Biblical infallibility. While biblical infallibility claims that the Bible is without error in every matter required for salvation, Biblical inerrancy claims that the Bible is without error in every detail possible, including scientific and historical details.

The distinction between Biblical infallibility and Biblical inerrancy matters because many people, when first confronted with the apparent contradictions in the Gospels, stop believing in central doctrines like the virgin birth and physical resurrection of Jesus.

When assessing ancient documents by normal historical standards, their reliability isn't determined by exactness in every possible detail:

The distinction between Biblical infallibility and Biblical inerrancy matters because many people, when first confronted with the apparent contradictions in the Gospels, stop believing in central doctrines like the virgin birth and physical resurrection of Jesus.

When assessing ancient documents by normal historical standards, their reliability isn't determined by exactness in every possible detail:

First, we may need instead to revise our understanding of what constitutes an error. Nobody thinks that when Jesus says that the mustard seed is the smallest of all seeds (Mark 4.31) this is an error, even though there are smaller seeds than mustard seeds. Why? Because Jesus is not teaching botany; he is trying to teach a lesson about the Kingdom of God, and the illustration is incidental to this lesson. Defenders of inerrancy claim that the Bible is authoritative and inerrant in all that it teaches or all that it means to affirm. This raises the huge question as to what the authors of Scripture intend to affirm or teach. Questions of genre will have a significant bearing on our answer to that question. Poetry obviously is not intended to be taken literally, for example. But then what about the Gospels? What is their genre? Scholars have come to see that the genre to which the Gospels most closely conform is ancient biography. This is important for our question because ancient biography does not have the intention of providing a chronological account of the hero’s life from the cradle to the grave. Rather ancient biography relates anecdotes that serve to illustrate the hero’s character qualities. What one might consider an error in a modern biography need not at all count as an error in an ancient biography. To illustrate, at one time in my Christian life I believed that Jesus actually cleansed the Temple in Jerusalem twice, once near the beginning of his ministry as John relates, and once near the end of his life, as we read in the Synoptic Gospels. But an understanding of the Gospels as ancient biographies relieves us of such a supposition, for an ancient biographer can relate incidents in a non-chronological way. Only an unsympathetic (and uncomprehending) reader would take John’s moving the Temple cleansing to earlier in Jesus’ life as an error on John’s part.

We can extend the point by considering the proposal that the Gospels should be understood as different performances, as it were, of orally transmitted tradition. The prominent New Testament scholar Jimmy Dunn, prompted by the work of Ken Bailey on the transmission of oral tradition in Middle Eastern cultures, has sharply criticized what he calls the “stratigraphic model” of the Gospels, which views them as composed of different layers laid one upon another on top of a primitive tradition. (See James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered [Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 2003].) On the stratigraphic model each tiny deviation from the previous layer occasions speculations about the reasons for the change, sometimes leading to quite fanciful hypotheses about the theology of some redactor. But Dunn insists that oral tradition works quite differently. What matters is that the central idea is conveyed, often in some key words and climaxing in some saying which is repeated verbatim; but the surrounding details are fluid and incidental to the story.

Probably the closest example to this in our non-oral, Western culture is the telling of a joke. It’s important that you get the structure and punch line right, but the rest is incidental. For example, many years ago I heard the following joke:

“What did the Calvinist say when he fell down the elevator shaft?”

“I don’t know.”

“He got up, dusted himself off, and said, ‘Whew! I’m glad that’s over!’”

Now just recently someone else told me what was clearly the same joke. Only she told it as follows:

“Do you know what the Calvinist said when he fell down the stairs?”

“No.”

“‘Whew! I’m glad that’s over!’”

Notice the differences in the telling of this joke; but observe how the central idea and especially the punch line are the same. Well, when you compare many of the stories told about Jesus in the Gospels and identify the words they have in common, you find a pattern like this. There is variation in the secondary details, but very often the central saying is almost verbatim the same. And remember, this is in a culture where they didn’t even have the device of quotation marks! (Those are added in translation to indicate direct speech; to get an idea of how difficult it can be to determine exactly where direct speech ends, just read Paul’s account of his argument with Peter in Galatians 2 or of Jesus’ interview with Nicodemus in John 3.) So the stories in the Gospels should not be understood as evolutions of some prior primitive tradition but as different performances of the same oral story.

Now if Dunn is right, this has enormous implications for one’s doctrine of biblical inerrancy, for it means that the Evangelists had no intention that their stories should be taken like police reports, accurate in every detail. What we in a non-oral culture might regard as an error would not be taken by them to be erroneous at all.

What Price Biblical Errancy? | Reasonable Faith

The limited inerrancy view offers room for the Bible to err in non-redemptive matters – matters that are not salvific by nature e.g. geographical, historical, scientific etc. The proponents of this view state that the main purpose of the Bible is “spiritual transformation” – to bring the lost man into a saving relationship with God. They then affirm that “If the Bible contains some errors, some discrepancies, that do not affect its power to transform lives through faith-filled communion with God, that is not important.” 3...

Bart Ehrman, the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, lost his faith in Christ because he apparently discovered one minor error in the gospels. It seemed Professor Ehrman held the doctrine of biblical inerrancy as the core of Christianity.

When a particular passage in the Gospel of Mark befuddled Bart Ehrman, his strong belief in inerrancy of the Bible was shaken. He became a liberal Christian and then ended up as an agnostic atheist after being unable to reconcile the philosophical problems of evil and suffering.

The Bible Has Errors, What Do We Do? - Christian Apologetics Alliance

Last edited: