Majority Text: (X): Carson's Objections Reexamined

Lets look at D.A. Carson's first objection to the Majority Text Probability Model:

He suggests historical factors skewed the results, supposedly making minority readings (errors/edits) become majority readings (overcoming the Alexandrian and other text-types). What mechanical model does he offer?

He cites:

Chrysostom comes onto the scene too late to explain the creation and existence of the Byzantine text. Born in 349 A.D., he was not even baptized until 368 or 373. He lived as a hermit from 375-377. He did not become a deacon until 381, and became a priest only in 386. Between 386-398 he became popular as a speaker/commentator, apparently in Antioch. He was ordained archbishop of Constantinople in 398. Because of his attempted reforms he was attacked and banished in 403, but reinstated. He was banished again to Georgia but died on the way in 407.

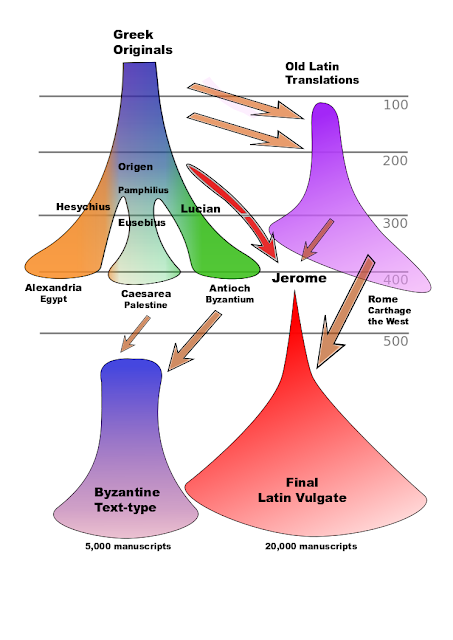

Chrysostom used the Byzantine text, but this was already the popular text in Constantinople by this time. He does not seem responsible for popularizing it himself. Jerome had used the Byzantine text for his Vulgate translation in 392, and had judged this text to be older than the three current recensions of

What about Carson's second idea?

Certainly the percentage of total manuscripts changed, with Latin manuscripts gradually outnumbering and even overwhelming Greek manuscripts:

Greek and Latin MSS: Click to Enlarge

However, both copying-streams were essentially separate, and both streams were normal. There is nothing in this situation that can explain a reversal of minority and majority readings.

Certainly the Latin MSS (Old Latin / Vulgate) already had essentially the same text as the Greek Byzantine MSS. This means that changes in the relative percentage of the MSS would not significantly affect the attestation of majority and minority readings.

The only thing that could happen from the change-over from Greek to Latin, is that a few of the so-called 'Western' readings would gain some support from the overwhelming numbers of Latin MSS. But this has nothing to do with the Byzantine readings in the Greek transmission stream. Very few if any Greek MSS in the Eastern Byzantine empire would ever have been corrected using Latin MSS! The Greeks couldn't care less about the Latin texts being used in the West.

Nor can the "shrinking" of the Greek language and influence cause any reversals between minority and majority readings. This is pure nonsense. The raw manuscript count went continually upward, as churches, people and markets, and demand expanded. What decreased here was the rate of increase, not the number manuscripts!

A 'shrinking' of influence would in any case cause a decrease in the score for Byzantine readings, not an increase! D.A. Carson's logic is what is really upside-down here, not the minority/minority readings.

Nazaroo

(to be continued...)

Lets look at D.A. Carson's first objection to the Majority Text Probability Model:

He suggests historical factors skewed the results, supposedly making minority readings (errors/edits) become majority readings (overcoming the Alexandrian and other text-types). What mechanical model does he offer?

He cites:

(1) the influence of Chrysostom,

(2) the restriction and displacement of the Greek language.

Because of this he argues, the Byzantine text probably doesn't represent the original text.(2) the restriction and displacement of the Greek language.

Chrysostom comes onto the scene too late to explain the creation and existence of the Byzantine text. Born in 349 A.D., he was not even baptized until 368 or 373. He lived as a hermit from 375-377. He did not become a deacon until 381, and became a priest only in 386. Between 386-398 he became popular as a speaker/commentator, apparently in Antioch. He was ordained archbishop of Constantinople in 398. Because of his attempted reforms he was attacked and banished in 403, but reinstated. He was banished again to Georgia but died on the way in 407.

Chrysostom used the Byzantine text, but this was already the popular text in Constantinople by this time. He does not seem responsible for popularizing it himself. Jerome had used the Byzantine text for his Vulgate translation in 392, and had judged this text to be older than the three current recensions of

(a) Lucian (Antioch, 270-310)

(b) Hesychius (Egypt, c. 320-350?)

(c) Origen (Caesarea, c. 200).

Even granting the popularity of Chrysostom's writings long after his death, this alone is simply not enough to cause or explain the dominance of the Byzantine text-type in the Eastern Empire. Hort had posed two 'recensions', first the Lucian (assuming this was the pre-Byzantine text), and then a second 'recension' in the 4th century. But who did a second major 'recension', and who imposed it upon the entire Greek-speaking world? Why was there no resistance, and more importantly, no historical record of this? Chrysostom is supposed to fit the bill, but there is no evidence that this ever happened. Chrysostom was a controversial figure in his own lifetime unpopular with the Emperor and many other bishops, and could not have imposed a uniform text in the East. (b) Hesychius (Egypt, c. 320-350?)

(c) Origen (Caesarea, c. 200).

What about Carson's second idea?

(2) the restriction and displacement of the Greek language.

How can this mechanism reverse the position of majority and minority readings? In fact, it can't. It is no mechanism at all. Of course the Latin language finally dominated Western Europe, while the Greek, formerly the dominant international language, faded from the stage. But this provides no mechanism to flip readings upside-down:Certainly the percentage of total manuscripts changed, with Latin manuscripts gradually outnumbering and even overwhelming Greek manuscripts:

Greek and Latin MSS: Click to Enlarge

However, both copying-streams were essentially separate, and both streams were normal. There is nothing in this situation that can explain a reversal of minority and majority readings.

Certainly the Latin MSS (Old Latin / Vulgate) already had essentially the same text as the Greek Byzantine MSS. This means that changes in the relative percentage of the MSS would not significantly affect the attestation of majority and minority readings.

The only thing that could happen from the change-over from Greek to Latin, is that a few of the so-called 'Western' readings would gain some support from the overwhelming numbers of Latin MSS. But this has nothing to do with the Byzantine readings in the Greek transmission stream. Very few if any Greek MSS in the Eastern Byzantine empire would ever have been corrected using Latin MSS! The Greeks couldn't care less about the Latin texts being used in the West.

Nor can the "shrinking" of the Greek language and influence cause any reversals between minority and majority readings. This is pure nonsense. The raw manuscript count went continually upward, as churches, people and markets, and demand expanded. What decreased here was the rate of increase, not the number manuscripts!

A 'shrinking' of influence would in any case cause a decrease in the score for Byzantine readings, not an increase! D.A. Carson's logic is what is really upside-down here, not the minority/minority readings.

Nazaroo

(to be continued...)